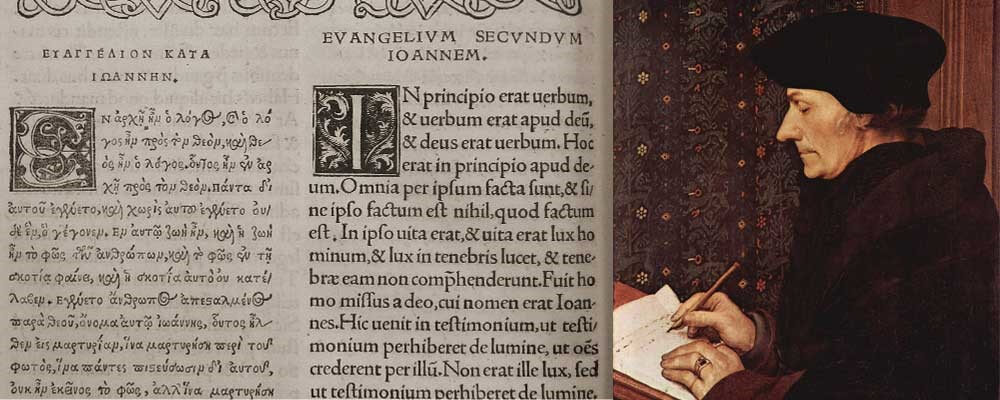

The Nordic Bible Museum’s collection includes one of history’s most influential editions of the Bible – the first printed New Testament (NT) in Greek, from 1516.

Novum Instrumentum Omne, as was its title, was published in Basel, Switzerland, by Desiderius Erasmus, known as Erasmus of Rotterdam. The book was bilingual, where the Greek text was presented in one column and Erasmus’ Latin translation in a column next to it, along with extensive comments in Latin. According to a leading expert in the history of the New Testament, Daniel B. Wallace, the Reformation was born as a result of Martin Luther having a copy of Erasmus’ Greek New Testament in his hands. Erasmus’ NT had a major impact on the course of history.

Background

Erasmus was born in Rotterdam in 1466 or -47 and was thus later known as Erasmus of Rotterdam. He was the illegitimate son of a Dutch priest and a housekeeper. His parents died when he was about 17 years of age. Erasmus wanted to attend university, but gave in to pressure from his guardians and joined a monastery of the St. Augustine order, where he studied Latin and read the works of the so-called Church Fathers [1] and the great writers of antiquity.

At the age of 26, Erasmus had the opportunity of leaving the monastery to become the secretary of the Bishop of Cambrai, which in turn led him to continue his studies at the University of Paris. However, he was very poor during his time in Paris, with many health issues (which he had throughout his life), and in addition to the fact that he seemed to disagree with his professors quite a bit, this made for a difficult period in his life.

However, in1499 he was invited to England where he became acquainted with Thomas More, John Colet and other leading English theologists. This strengthened his decision to concentrate on studying the Bible. To get a better understanding of the message of the Bible, he immersed himself in studying the Greek language, and in the year of 1500 he returned to Paris to further his education in Greek. In a time where the life expectancy of men was about 40-50 years of age, there were those who reacted to him starting his Greek studies at the mature age of 32. Erasmus himself wrote this to a friend: “One might ask why I… learn Greek at my age… I am quite certain that it is better to learn something late than to remain lacking in essential knowledge.”

In 1504, while living in Leuven, Belgium, in an attempt to avoid the ravaging plague at that time, Erasmus became familiar with a manuscript by Italian Lorenzo Vallas with comments on the New Testament. This collection of comments on the Latin Bible translation, called Vulgata, awakened his interest in textual criticism [2], and Erasmus decided to attempt a reconstruction of the original text of the Bible’s New Testament.

After this, Erasmus stayed in Italy a few years before returning to England. He continued his work enhancing the text of the New Testament while teaching Greek at the University of Cambridge.

Erasmus was very concerned with actually understanding the Bible, which becomes clear in his book from 1519 called Ratio Verae Theologiae (“Method of True Theology”). In this text he explains his method for Bible study and provides guidance on how to interpret the Bible. For example, Erasmus says that one should never take a quote out of context, or separate it from the connected thoughts of the author. He saw the whole Bible as one. The interpretation should therefore come from within, and not from anything outside of the Bible itself. This is why it was essential that people could actually read the Bible themselves, in a language that they could understand. In his preface to the New Testament, Erasmus wrote: “I totally disagree with those who do not wish for common people to read The Holy Scriptures, and who would not have them translated into the people’s own language.” Ironically, he wrote this in Latin, a language “common people” could not read.

[1] The “Church Fathers” are ecclesiastical writers in the Classical and early Middle Ages whose works are considered authoritative in Catholic and Orthodox denominations.

[2] Textual criticism is the philological examination of a text with the intention of revealing its historic development. Different versions of the text will be examined in the process. The textual critic will reveal how the text, whether intentionally or by chance, has changed over time, and where to place the different text witnesses in this development.

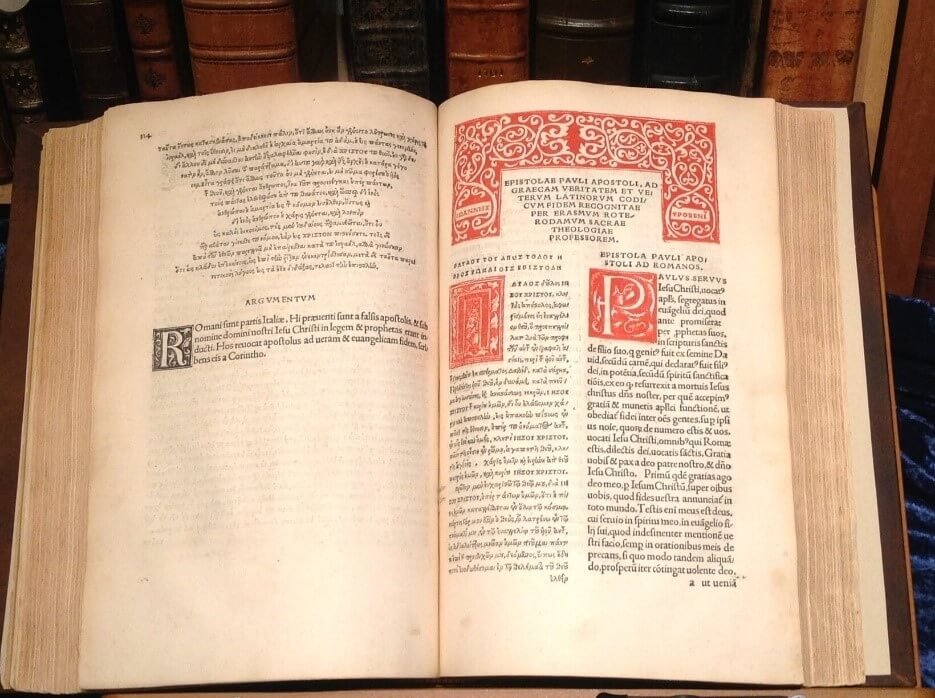

The first New Testament published in Greek

A printer in Basel, Johannes Forben, was eager for Erasmus to finish his work on the Greek text. Forben knew that the Spanish Cardinal Jimenez had printed the New Testament in Greek and Latin in the year 1514, but that he had not published it yet. He wished to complete his work on the entire Bible before publishing any parts of it. In 1522, five years after the cardinal’s death, the complete work was published as Biblia Políglota Complutense (“The Complutensian Polyglot Bible”). Erasmus’ version of the New Testament, however, was published in 1516, and thus became the first ever published version of the New Testament in Greek. The title was Novum Instrumentum Omne (“A Whole New Instrument”).

Erasmus and Forben took a big risk when they published Novum Instrumentum without the written approval of Pope Leo X. In an attempt to please the Pope, Erasmus wrote in the preface that his work was dedicated to the Pope himself. The printing started in August 1515 and finished in March 1516, with over 1200 copies in folio format.

Despite the fact that it was printed two years after the Complutensian Polyglot, which had a much better Greek text, Novum Instrumentum became the first text on the market, as it was the first to be published. Being both quite cheap and relatively small (unlike the Polyglot, which was neither), it became very popular. When the Polyglot eventually reached the market, Erasmus had already published a third edition of his work. Furthermore, a large shipment of the already limited, 600 copy edition of the Polyglot got shipwrecked, and the work was thus made a rarity almost immediately.

In his preface dedicated to the Pope, Erasmus claimed that the manuscripts he used were “very old and very correct” – while in reality they were neither of those things. He compiled his Greek text on the basis of no more than six handwritten manuscripts, and none of these were dated any earlier than the tenth century AD. The printer mainly used only two of these manuscripts, dating from the 12th century. Not only was the number of sources very limited, but these editions were written over a thousand years after the original New Testament came to be.

The Book of Revelation was the part of Erasmus’ work with the least source material. Not only was it based on just one manuscript, but that manuscript was even incomplete. The last page with chapter 22 verses 16-21 was missing. Instead of acquiring a complete manuscript, which would cost him precious time and money, Erasmus simply translated the missing passage from the Latin Vulgata edition into Greek, making several mistakes in the process. This inadequate version even remained unedited through all five editions that were published in Erasmus’ lifetime, although he most definitely would have had the opportunity during those 20 years to obtain a complete manuscript to replace his own, faulty translation.

As the completion of the Novum Instrumentum had been rushed, there were several other mistakes as well, many of which were corrected by Erasmus himself in later editions. He was the first to develop the idea that the most difficult reading is the oldest one, and this guided him in his critical analysis of the Greek text.

Consecutive editions

The second edition, from 1519, changed the name to Novum Testamentum and corrected many typos, but the text itself remained almost unchanged. In 1521, four years after Martin Luther made his theses public in Wittenberg, he was excommunicated by the same Pope to whom Erasmus had dedicated his Novum Instrumentum. Luther then translated Erasmus’ New Testament to German in just ten weeks, and published this in 1522 – the first translation from ancient Greek to a modern language.

The third edition of 1522, is famous for including the so-called Comma Johannum (an addition in 1. John 5:7-8). Erasmus was convinced that this passage was not in the original text, but rather an addition from the Middle Ages. Why he then decided to include it in the third edition is unknown, but it was most likely due to both pressure and a desire to reach a broader audience. Since Luther based his translation on the second edition, where the passage was not included, it was never a part of the Luther Bible. William Tyndale, however, based his English translation on both the second and third editions of Erasmus’ text, as well as Luther’s translation, and chose to include the passage in his 1526 edition of the New Testament. That way it also became a part of the King James Version (1611), the most printed and widespread book in the world.

Erasmus’ fourth edition was published in 1527, and it showed signs of influence from the now published Complutensian Polyglot, especially in the Book of Revelation. The fifth and final edition came as late as in 1535, the year before Erasmus died. Over 300.000 copies were in circulation in Erasmus’ lifetime alone, and it was re-printed at least 69 times between 1516 and 1536.

The Importance of Erasmus’ New Testament

As we have seen, both Luther and Tyndale translated the New Testament based on Erasmus’ Greek text. When we consider that their translations became the most widespread and influential in history, a position they still hold even today, the importance of Erasmus’ New Testament becomes quite clear.

During the 18th century, Erasmus’ text became known as Textus Receptus (the Received Text). All important Protestant translations of the New Testament that were published before 1881 are based on this Greek text.

Even though Erasmus’ text had its faults, it brought with it the beginnings of extensive textual criticism, which has led to the more precise Bible translations of our time. Following the later discoveries of many older manuscripts than those available to Erasmus, new publications of his text often include a system of footnotes showing where and in what way older sources differ from his.

Erasmus only had a few manuscripts to work with, whereas today we have a thousand times that. Centuries of new discoveries and extensive textual criticism have resulted in editions of the Greek text that are much closer to the original than what Erasmus himself could produce.

Aftermath

Not everyone was happy about Erasmus’ work. Especially so since he was very critical towards the clergy in some of his commentaries. One example is Matthew 16:18: “you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church”. Erasmus did not believe these words to be exclusively used for the Pope, and he rejected Peter’s supremacy. Bravely done, especially in a text dedicated to the Pope himself. It is perhaps no mystery, then, why many of Erasmus’ works ended up on the Vatican’s List of Prohibited Books.

On the 8th of April 1546, the Church Council in Trent approved the Vulgate [3] as the official Bible of the Catholic Church – while Erasmus’ New Testament was condemned. This is why later translations of Erasmus’ work are primarily Protestant. For example, the first Norwegian Catholic translation of the New Testament in 1902 was based on the Latin Vulgate, while the Norwegian Bible Society translated the NT from Greek two years later.

Erasmus fulfilled his desire and hopes that he had written about in the preface to Novum Instrumentum: «I wish I could get these words translated into all languages… I long for the day when the plow boy shall sing them as he walks behind the plow».

Erasmus lived to see his Greek text translated into German (1522), English (1526), Swedish (1526), Italian (1530) and French (1535) before he death in 1536 (Spanish followed in 1543). Now most Europeans who were able to read could finally read the New Testament in their own language, just as Erasmus had wished for.

[3] Ever since the 13th century, the Vulgate was the name of the Latin Bible translation commonly used by the Catholic Church since the 7th century. The Vulgate is mainly based on a translation made by Hieronymus (382-405), commissioned by the Pope to replace the existing translations called Vetus Latina, which differed greatly from one another.

Online Facsimiles

See the first editions for yourself here: 1516-edition, 1519-edition and 1522-edition.

Sources and further reading:

Erasmus, Desiderius, og Heinz Holeczek. 1986. Erasmus von Rotterdam Novum instrumentum: Basel 1516. Faksimile-Neudruck mit einer historischen, textkritischen und bibliographischen Einleitung von Heinz Holeczek. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Frommann-holzboog.

Combs, William W. 1996. “Erasmus and the Textus Receptus.” DBSJ 1: 35–53.

Goeman, Peter J. 2016. “The Impact and Influence of Erasmus’s Greek New Testament”. Unio Cum Christo. April 2016.

Wallace, Daniel B. 2016. “Erasmus and the Book That Changed the World Five Hundred Years Ago”. Unio Cum Christo. October 2016.

Wikipedia-artikkel om Erasmus.

Wikipedia-artikkel om Erasmus’ NT.

Wikipedia-artikkel om «Textus Receptus».